- Home

- Simon Reeve

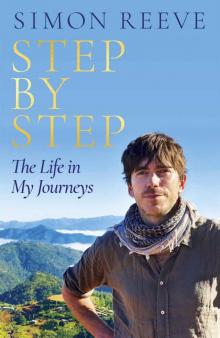

Step by Step Page 21

Step by Step Read online

Page 21

‘Crown Prince, Crown Prince,’ I said, pushing past a bodyguard with an assault rifle. ‘Simon Reeve from the BBC, please could we have a word?’

He turned and looked at me patiently. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he said. ‘I have the King of Jordan in the other room, and I cannot keep him waiting.’

As excuses go, it was strong.

Still, my journey gave me a vivid insight into the kingdom. I finished my travels down near the border with Yemen. One night in the Empty Quarter desert, in an ancient corner of the world and under stars so bright I could read by their light, my otherwise silent bodyguard suddenly started tapping away on a hand-drum and sang a haunting song to the moon. It was completely spellbinding.

These programmes were all interesting to film, but I was itching for more travelogues like Meet the Stans that blended the light and the shade. Safely back in London, I put together proposals and plotted more adventures.

Then one summer night I went with my friends Ben and Antoine to a publishing party held to celebrate the launch of The Coma, a book by Alex Garland, author of The Beach. I was out most nights at the time when I was in London, socialising, going to parties and generally living the life of a single lad. I drove friends like Mike, Maurice and Dimitri mad with some infuriating rules which meant that if I walked into a bar or a party and there was no one I or they thought was interesting I would often turn around and try to persuade everyone to go somewhere else. Arriving at the packed publishing party, Ben turned to me and said: ‘At least let’s have a drink.’

I was just inside the door when I saw her. Towards the back of the party, at least 15 metres away, was a tall, elegant, laughing woman with tumbling blonde hair who stood out in the crowd so instantly it was as if she was lit by a spotlight. She was talking to a couple of men in a way that suggested they were both trying to flirt with her. She looked bright, open, interesting, and she was gorgeous.

Another of my dating rules was no ‘cold-calling’ at a party. I wouldn’t just wander over to someone and start chatting them up without at least a tiny indication of interest. It was partly tactical, partly about not hassling lone women, and largely about ego. If there was a second glance then all risks were dramatic-ally reduced. I haven’t even mentioned my rules about no Scandinavians, no only children, and no cats.

I moved through the crowd to get a drink, casually keeping my eyes on her, and then as I went to pass in front of her I willed her to look in my direction. It worked. Anya glanced up, our eyes locked, and I smiled. Everything slowed. She held my glance for a wonderful second longer than was merely polite, something fizzed, and I Knew.

Life is always built on tiny moments of chance and circumstance. If her back had been turned, if . . . I got a drink and stood with the lads. ‘So you’re staying then?’ said Ben and nudged me in the ribs.

I can’t say it was love at first sight. I wasn’t a teenager. I thought she was stunning, but looks aren’t everything. The Japanese have a word for the feeling that suddenly erupts when you meet someone and know you are destined to fall in love. That was close to what I felt in that moment. I felt excited and confident, but bided my time. Anya was engrossed in conversation with her friend Leanne.

A couple of drinks later and Ben and Antoine were getting impatient.

‘Go on,’ urged Ben. ‘She won’t stay here all night. Go and talk to her.’ Then he gave me a gentle shove in the right direction.

One of our first dates was lunch in the restaurant inside the British Museum. Anya had been living in Denmark for the past few years. She was half-Danish, spoke fluent Danish, had a degree, worked as a model and had been a camerawoman on wildlife documentaries. She was opinionated, thoughtful and funny, telling tales about a horrific shoot she abandoned when a producer started gluing stick insects to a branch in a garage in Croydon. When we met she was working for her friend, a chess grandmaster from Bolton who used to captain the British chess team, developing links between universities and industry. As we left the restaurant I walked us out past the Rosetta Stone, an ancient slab of rock inscribed with three versions of the same boring decree – one in Egyptian hieroglyphics, another in Egyptian script, and the third in Ancient Greek. It was found by Napoleon’s forces, I told her casually, trying to impress her, and used in the nineteenth century to finally decipher Egyptian hieroglyphics and much about the Ancient Egyptian world.

Anya was listening to me thoughtfully.

‘Yeeees,’ she said slowly, straining her eyes to see the top of the rock. ‘It says . . .’

And then she began reading the Ancient Greek on the stone aloud. I was completely bowled over. Some tourists standing next to her turned and gaped.

‘How . . . ?’ I stuttered.

‘Oh, erm, I’m fluent in Greek,’ Anya said, all very matter-of-factly. ‘And I can read it. I lived there for a while.’

‘But . . . ?’ I stuttered again.

‘It’s Ancient Greek, but still Greek,’ she shrugged. ‘Amazing, isn’t it, that the language still has enough similarities after more than two thousand years?’

‘Anything else you haven’t told me?’ I said.

‘Well, I speak a bit of Arabic,’ she said brightly.

And then she realised people around us were staring. She blushed just a little and started to move away. Well, reader, I have to say, I was completely smitten.

One night a couple of weeks later I was in a pub with a few friends having a drink after a game of football under the Westway in West London, just near Grenfell Tower. One of them worked as a shipping agent. He was telling a story about sending some equipment via a place called Somaliland. I cut in.

‘Sorry, where? Somaliland?’ I said. ‘Where on earth is Somaliland?’

‘It’s in the horn of Africa. It’s not a recognised country, but I’m trying to send a container there.’

An unrecognised country, I’d never heard of such a thing. How could a place like that exist? Something sparked inside me. I grabbed a pen, scribbled the word ‘Somaliland’ on a scrap of paper and stuffed it into my pocket. Then I had a couple more drinks. Of course, I forgot it was there. I wandered home, woke up in the morning, discovered the note and wondered what on earth it was. Then I remembered the conversation, sat down at my computer and discovered it wasn’t the only unrecognised state. There were scores of them. All places that technically did not exist.

Although there are almost 200 official countries in the world there are also dozens more unrecognised states like Somaliland which are determined to be separate and independent. These countries are home to millions of people, they have their own rulers, armies, police forces, and issue passports and even postage stamps, but they are not officially recognised as proper countries by the rest of the world. So they can’t send a team to the World Cup, have a seat at the United Nations, or even send a singer to Eurovision.

I was fascinated. The more I looked online the more I found. There was a whole stack of unrecognised states with defined borders, governments and infrastructure that weren’t officially recognised as nations. When I put them all together I realised there were more than 250 million people who lived in unrecognised countries or considered themselves unrepresented people. Within half an hour I knew this could be a new series. It was an entirely new subject area that nobody knew much about.

Soon I was engrossed in research, and Anya was a massive help.

Together we read up about unrecognised countries and unrepresented people. Both of us thought they were completely fascinating. Each place that we found sounded exotic and unknown: Abkhazia, Assyria, Batwa, Crimean Tatars, East Turkestan, Hmong, Iranian Kurdistan, Khmer-Krom and Ogaden. How can anyone even read the names without booking a flight to learn more? What about Oromo, South Moluccas, Talysh, West Balochistan, West Papua or Western Togoland? Then we discovered a group called the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO), which formed some sort of umbrella group for countries that couldn’t get into the United Nations. While the UN had a grand

headquarters next to the East River in Manhattan, the UNPO had an office in The Hague. But they had an annual conference coming up in a few weeks. Anya and I looked at each other. We had to go.

I booked tickets, Anya packed her camera gear and we found somewhere to stay. My friend Jo lived in The Hague and said we could use her flat. We arrived to find His & Hers toothbrushes in the bathroom ready for us and rose petals scattered across our bed.

As a quirky destination for a romantic break, the conference in The Hague was simply brilliant. I had never been to a more obscure gathering. Representatives of the most exotic and often persecuted people in the world marched through The Hague and then took their places at a huge circular table that looked like something out of Camelot. Anya and I had a long chat with people from British Cameroon and Nagaland. Then the Crimean Tatars played the Hmong at football.

Talking to the different country reps it was clear to me this was a huge, forgotten story. Almost all of the unrecognised countries were at the centre of past or present conflicts, or were likely to be caught up in an armed struggle in the future if nothing was done to resolve their status. These were people fighting for independence and identity with a voice no one was hearing, even though every tale was strong and emotional, every speaker erudite and committed. There was little interest from the mainstream media. There was no TV coverage of the conference. Anya filmed it for our research and there were a couple of students doing something similar, but that was it. The UNPO was largely unknown. It was a hidden story about our planet.

Back in London we collated all the information we had and put together a list of the unrecognised places around the world that best represented the issues we had heard. Our plan was for me to go on a series of journeys to some of the most obscure places and shine a light on their stories. We turned it into a TV proposal and sent it off to the BBC. Before we knew it, I was back at TV Centre. My second series of travelogues had been commissioned. It was to be called Places That Don’t Exist, and against stiff competition it remains one of my absolute favourite and most memorable adventures.

There is a certain excitement to arriving somewhere without a clue where to stay or what to do. If you travel spontaneously you often put more thought and consideration into the journey on arrival because you are not following some predetermined tourist trail. You know memories will not be served on a plate, and you have to find them yourself. Spontaneity also means you can wander around a city or a resort area and decide where you want to stay based on reality rather than an enhanced photo on the internet.

Early in our relationship Anya and I booked tickets at the airport and headed to Sharm el-Sheikh, the Egyptian resort town on the Red Sea, for a last-minute break. We walked along the promenade and lazed on the beach for a couple of days, then got bored and took off into the desert. We bought meat from Bedouin, slept out under the stars and then took a daft turn in our little hire car on a complete whim and sank into deep sand in the middle of the desert. It was my fault. I hopped out of the car, looked around for a few moments and realised we were miles from help, then heard a worrying sound coming from the other side of the car. Anya was already down on her knees digging out the wheels and letting the tyres down so we could escape.

‘Come on,’ she said. ‘Let’s get on with it.’

Even today our strongest memories of that holiday are the hours we spent digging out the car together. That bonding experience became part of the glue for our relationship. If you want to have a spontaneous adventure, it’s always worth remembering that some of the most memorable times can happen when things go a bit wrong. But I still try to follow simple rules: I don’t arrive anywhere late in the evening because I want some time to have a look around before finding a bed. I travel light, put cash in my sock, don’t get too hung up on review sites, and I try to avoid following the crowd, so I can have my own experiences. Plus I say yes to almost everything.

You can start locally. Upturn a glass on a map and centre it on your home. Then draw a ring around the rim and explore that circle so you know it like the back of your hand. All travel gifts memories, and spontaneity has a place. On my TV programmes we don’t write a script in advance and we don’t usually have a recce. I don’t take a list of questions with me and I am not fed things to say through an earpiece. Spontaneity is encouraged. Much of the time when we are filming we have to make it up as we go along, which can be exciting but also nerve-wracking. If we are set to film a monument in the centre of a city and then spot a demo nearby we will always make the more exciting choice. Hopefully the programmes feel more real as a result.

However, we still need to plan a TV adventure before we go to ensure we reap the full benefits of a trip. We spend at least a few months preparing where we might be able to go and what we might be able to see and do for each shoot or series. Arriving somewhere without a clue about what we are going to do would be profligate. Careful planning and preparation guarantees powerful experiences.

Every journey is different and every production team works differently, but generally an assistant producer or researcher will start drawing up a list of possible stories and adventures two or three months before a shoot actually starts. They use the internet, guide books, newspaper articles and long, long conversations with guides and experts in the countries we are heading towards. Meanwhile we will have meetings, drink tea, look at maps and debate the merits of locations, routes, stories and people we could meet. There are no hard rules for what makes it onto the final list of what we film, but we aim for extremes, whether extremely beautiful, thrilling, shocking or inspiring. I also try to use a technique that has worked well for me in relationships: if someone believes really strongly that we should do something, whether it’s the assistant producer or the executive in charge, we generally do it. Enthusiasm trumps apathy. In my relationship at home we sometimes rank things out of ten. Don’t laugh. One of us might idly suggest going to see something, and the other isn’t entirely keen. The proposer admits they only want to do it ‘level five’, which means they really aren’t that bothered, whereas the opposer says they really, really don’t want to do it, ‘level eight’. It generally works. You have to be honest and you can’t keep dropping level nines or tens, because you just sound mad. Give it a try. Even my long-suffering television colleagues have occasionally played along.

While discussing and debating the ideas for TV shows, the potential shooting team are contacted to check availability, then visas are organised, equipment hired, arms are jabbed with vaccinations, and risk assessments are completed. Eventually we get on a plane.

At the start of Places That Don’t Exist my first destination was the largely unknown breakaway state of Somaliland, the inspiration for the entire project. A series of trips would also take me to Transnistria (between Moldova and Ukraine), Taiwan, Nagorno-Karabakh, also known as Artsakh, a landlocked region in the South Caucasus, and three regions of Georgia which broke away after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was a chance to visit some of the most obscure and forgotten parts of the world.

All of the unrecognised nations on my list declared independence after bloody conflicts with a neighbouring state, which I also wanted to visit. In the case of Somaliland, that’s Somalia, one of the poorest countries in the world and at the time perhaps the most dangerous.

I went in with a small team. Just Shahida, my colleague and guide in Uzbekistan, and a producer-director called Iain Overton, a Cambridge graduate who had just been in Iraq filming a frontline fly-on-the-wall documentary about the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in Basra. He was ideal for the job, but we didn’t actually meet until we were at Heathrow.

Shahida had become a feisty friend, brilliant travelling com-panion, and assistant producer. She was perfect because she was brave, had a no-nonsense approach to officialdom, and was pre-pared to take the calculated risks required to go somewhere tricky so we could share the experience with the viewers. There are very few jobs I can think of where you meet one of the people you’ll

be travelling with into a volcano just as you step off the rim. But that’s how it felt on that shoot. I knew Shahida well, but Iain and I hadn’t been bloodied together.

That probably sounds dramatic, but flying into somewhere dangerous you need to know what your team can cope with, how they will react in tricky situations, and whether you can trust them to have your back should things go badly wrong. You need to know whether they will carry you, and whether they will literally give you their blood.

We were heading to Somaliland but first we needed to visit neighbouring Somalia and its capital, Mogadishu. According to reports, it was in a state of near chaos with gun-toting young men on the streets. For years there had been conflict and civil war and the country was in a state of collapse. Kidnap and murder were serious risks. Warlords were feuding over disputed territory. We would need to hire a team of local mercenaries to protect us. As one of the most volatile places in the world the BBC classed it as a ‘category one hostile environment’, and a place of ‘exceptionally high risk where battlefield conditions prevail’. Going there would be the most dangerous journey I had undertaken.

The difference between this adventure and Meet the Stans was that this had been my idea from the start, whereas my previous travelogue had been the product of discussion and debate. It wasn’t to be a single long journey, it was a series of smaller trips, but still through often tough terrain. We would be off the map, quite literally, and first we had to get through Somalia.

Step by Step

Step by Step