- Home

- Simon Reeve

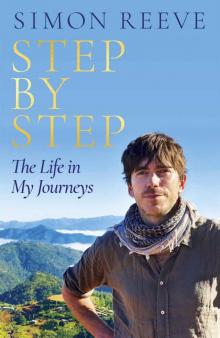

Step by Step Page 3

Step by Step Read online

Page 3

Ours was a small family. Both my parents were only children. James and I had no first cousins, no uncles, no aunts and no grandfathers. When I was five my dad’s mother Delsie died. But my Grandma Lucy was a rock of love through my early life with a cosy home nearby in West London that was a loving refuge. Gran was large, cuddly and always ready with a hug and some home-made cakes, especially when life was challenging or things were difficult for James and me at home.

I don’t come from a connected family. I didn’t grow up in wealthy Westminster or Chelsea. I didn’t go to private school or Oxbridge, and I wasn’t commissioned in the forces. Nobody in my immediate family has ever gone to university. Go back just a couple of generations on my dad’s side and they were fish-hawkers traipsing door to door. One generation further and they were child labourers with no education at all.

Some of my earliest adventures were when my grandma, who for years wore a caliper on her leg due to childhood polio, and always found walking a struggle, would take James and me on magical mystery tours in her adapted car. My gran inspired me when I was a child and her memory remains with me and guides me as an adult. James and I would sit on booster seats and direct her left or right down one street after another. It was completely thrilling, exploring exotic areas like Hounslow, or Park Royal Trading Estate. Gran loved the freedom to drive, and for me, directing a car at the age of six was a real power. I can still remember the sense of excitement as we peered out of the window and discovered the McVitie’s biscuit factory from the back of Gran’s converted Ford Escort. I don’t think I’ve ever quite lost that thrill of discovery, of seeing what lies over the hill, or round the next corner. I have my gran to thank.

My second favourite treat as a kid was our monthly family meal out. All dressed up in Sunday best, we’d go to our local church, then drive to a huge Makro cash and carry, stack the boot of the car with wholesale quantities of potatoes, baked beans and toilet roll, then troop to the Makro canteen where plates of chewy beef and two veg had been waiting, possibly for a while, behind Perspex pull-up windows. Sunday was bulk-buy day for the small-store and corner-shop owners in West London, and we must have looked ridiculously out of place, but it was what we could afford, and the lemon meringue pie was delicious. A proper Harvester restaurant or Berni Inn was reserved for really special occasions.

My early horizons were local. I had a parochial view of life on the periphery of the most exciting city in the world. I went to the school near the bottom of our road at first and then a couple that were just a bus ride away. Holidays took me a little further. Year after year we went to Studland Bay in Dorset, where the waters of the English Channel lap a sandy shore that drifts for mile after mile. It was almost a pilgrimage. Dad had seen an ad in a magazine for a house rental near Studland in the small market town of Wareham. The owner was offering it ludicrously cheaply. He only advertised once, and he never raised the price, so we just went back again and again. Every day was the same: we would make a packed lunch, climb into our old Volvo and race down roads packed with holidaymakers. Dad loved overtaking. Once he managed to zip past eight cars in one go on a long straight. That was his record. What was he thinking? No wonder the engine blew up. We’d get to the beach and put up our deckchairs in the same place on the beach, every day, every year, as if it was our patch of sand. James and I spent hours exploring every inch of the dunes, and we were in the sea so long our skin was as wrinkled as wizened old men. At the time it was idyllic. Studland was a gorgeous bit of coast, and we went crabbing, swimming, climbing and digging. It was the 1970s. People didn’t travel abroad the way they do now. We went across the Channel once when I was a child – on a camping holiday to France, Switzerland and Italy. I didn’t get on a plane until I started working.

My parents had travelled a little further before they had us kids. They went on a cruise on the Med, and Dad took a party of children from his school skiing in the Alps in the late 1960s. Taking state school kids from a poor area of London abroad, let alone to the slopes, was almost unheard of at the time, but Dad was stubborn and determined to make it happen. A first-timer himself, he spent an age lecturing them on the dangers of skiing and how they needed to take it slowly and carefully. He was on the slopes for less than twenty minutes before he fell badly and snapped his leg in two places. The break was so bad he needed a thick metal pin almost a foot long inside his leg to hold it together. We still have it in a drawer in the house in Acton. After it was taken out of his leg Dad used the pin to stir the sweet home-made fruit wine he would make every year from cheap powdered kits you could buy in Boots the chemist. Huge old pots steamed on our cooker, then glass demijohns full of Chateau Reeve sat on top of the kitchen cupboards, popping as they fermented. Bottling and labelling the wine was a ritual, creating cheap and cheerful presents for Christmas. Dad swore his metal rod gave the wine an extra kick.

If there was anything specific that really helped to inspire my adult love of discovery and my interest in the wider world and our billions of stories, it was our local church when I was a small child. We weren’t a particularly religious family, and I don’t go to church now, but there’s no doubt the exposure I had to life at Acton Hill Methodist Church shaped me. But initially it was just a playground. As a tot I was fascinated by a steep cast-iron spiral staircase that led up to the organ loft. Every Sunday I would scale and play on the steps until I finally plucked up the courage to swing down on one of the support poles. Nobody stopped me, nobody worried, it was completely fine for kids to have the run of the place, because it was a community centre and extended family.

By the time I was five Mum says I was a thoughtful lad who would take a knife and chop individual Smarties into four pieces to share among my family, which perhaps suggests my parents had a lax approach to knife safety and I didn’t have enough sweets.

From the age of six or seven I was an inquisitive little soul asking tricky questions about the biblical books we were given in Sunday school. My parents passed me on to the minister, an enlightened man who told me he didn’t have all the answers and that it was OK to ask questions. There was never any sense of submit and obey. The church gave me the confidence to query. So when religion told me that anything was possible if your faith was pure and absolute, that if you believed something fervently enough it could happen, I decided to put it to the test.

On our next holiday at Studland I stood by the sea screwing up every ounce of belief I could muster, telling myself that if I believed hard enough I would be able to walk on water. I took it seriously. Eyes closed fast, I lifted a foot and let it dangle above the lapping waves before trying to take a step. I told myself I could do this. I could walk on water.

I stood there for an hour. Sadly gravity was against me. It was shattering. No matter what I’d been told, belief was not enough and never would be. It was a mad thing for a seven-year-old boy to do, but that was the day I lost my faith and it has never returned. It was important, a moment when my sense of childhood wonder cracked. I couldn’t walk on water, so I never really listened when people at church talked of faith. But I had never really been interested in the service anyway. It was the playtime, friends and stories from the congregation that I loved.

Compassionate and constructive, the church was more like a gathering of UN volunteers than a congregation. Acton was almost ludicrously diverse, and the church doors were open to all. Dozens of countries were represented and national day, when the congregation wore national costumes and clothing, was as colourful as a carnival.

When I was young Mum and Dad would regularly invite lone visitors to the church over for Sunday lunch, so we had a procession of people sharing their stories. George, a research scientist from Ghana, stood out. He was studying the best vegetables for growing in sub-Saharan Africa and was championing the sweet potato as the best option for reducing poverty and hunger. I remember him holding a gnarled old chunk up to the light as if it was sacred and talking about the desperate suffering he’d seen travelling in West Africa.

He had me spellbound. Sweet potato became a staple in family meals for years after.

Our house was never full of friends. By the time I was in my teens I was at war with my father and most people stayed away. But when I was still a child other teachers from Dad’s school would visit. There was Uncle Ian my godfather, Uncle Eddie the art teacher, a wild-haired Aussie with a glint in his eye who would tell James and me tales of his travels in the outback, and Uncle Angelo from Sri Lanka, a bull of a man. He told us about tensions, uprisings, and what the Brits had done to his country. He brought tales to our table I had never heard before.

There were also talks in the church that somehow my parents persuaded me to sit through. In one a couple of white aid workers and their young son came to visit and described the wonderful colour blindness of children. Their son was blond-haired and blue-eyed and he had been educated in an African school where every other child was black. His mother described to us how one day when he was roughly five years old he told her they had a new teacher.

‘Mum,’ he’d said. ‘I was just sitting there when the new teacher came in and none of us had seen him before. He looked straight at me and said, “You must be Peter.” Well, how did he know my name? Nobody told him. How did he know I was Peter?’

Of course, Peter had been the only white face in the class. I was nine when I heard the story. Even at that age I could see how funny this was but also how profound. I was growing up among every creed and colour and hearing horror stories about racism and discrimination. The wonder and the beauty that skin colour never occurred to younger Peter struck a huge chord. I see it now in my own son Jake, who will mention what people are wearing to identify them rather than their skin colour. We’re not born racist. As kids we’re all just human.

Other talks and sermons at the church focused on natural disasters, war or suffering. Much of the world was represented in the congregation, and whenever something awful happened elsewhere there was usually someone with a personal connection to the issue or area. Speeches were given. Tears flowed. Money was raised. Then every year we’d have a dedicated week of fund-raising where my family of four would stuff charity envelopes through doors in streets near our home for a specific campaign. James and I would work each side of a street, ducking in and out of gates and crawling through hedges in a race with the other. The envelopes came with mini leaflets that I’d read and studied. They gave me an understanding and appreciation of my own good fortune. I was raised to be mindful and I’m grateful for it. No doubt it sounds worthy, even cheesy, but even at a young age, before I was ten years old, the church, the congregation and fund-raising helped me to realise there was a huge, extraordinary world out there often haunted by an immense amount of suffering.

My mother says I was eight when I told her about global warming. I doubt I could have grasped that concept at such a young age, let alone described it. It’s more likely I was telling her about the hole in the ozone layer. TV programmes and teachers were talking about the issue by the very early 1980s. Whatever the issue, Mum says what struck her most wasn’t the fact I knew about it, but that I cared about the consequences. I’ve tried to keep that sense of concern and empathy and not allow the world and its endless horrors and cynicism to strip it away.

I can’t claim to have many skills, but when it comes to engaging with people I hope I’m able to empathise without being patronising. When someone tells me their story I really feel what they’re going through and can work myself into a complete state internally. I feel it viscerally, deeply. I don’t know if that empathy was born of talks in church or wiring from birth, but it was certainly shaped at a young age, and then fed further by hurdles and challenges later in life. I never want to lose it. That early awareness helped to teach me a person’s plight or circumstances at any one time should never serve to entirely define them.

By the time I was ten I told my mum I wanted my life to mean something. That I wanted to count. But we were an ordinary, hard-working family and I grew up with no idea of what I would do with my life and no real horizon beyond my corner of Acton. My main ambition was to be a van driver. Then I thought about being a policeman. I was getting serious. Maybe a bit too serious. But then I was given a BMX as a birthday present and I became a little tearaway.

CHAPTER THREE

Mr G. Raffe

Historians say one of the most significant developments in the lives of ordinary Brits was the invention of the bicycle. Suddenly farm workers and villagers had a cheap way of moving large distances, widening their eyes, their world, and our gene pool. Bicycles transformed Britain.

Nothing broadened my horizons as a child faster than my BMX. By the age of eleven I was on two wheels and exploring Acton and the parks and estates of White City. At the same time James and I were taking the 207 bus every morning from Acton to our school in Ealing Broadway, a 20 minute journey away, with a huge group of other kids, many of them older and infinitely naughtier. The bus journey became like crime academy, with the older kids teaching and encouraging my brother and me how to skive off, muck about and misbehave. Bunking the bus fare was the entry-level game. Those were the days of the old Routemaster double-decker with a conductor and an open deck at the back with a grab pole.

A conductor would approach for a fare and I quickly learned how to glance around completely innocently, with perfect timing, and smile with my eyes. I had just the right air of confidence. He or she would pause for a second and more often than not suddenly seem to remember I’d already paid. Among our group of kids who took the bus together I became one of the best at bunking the fare. I was disarming, and I became a good liar. Even if the wiliest conductors made it past my smile they could still be fooled.

‘Ticket?’

‘It’s right here.’ I’d fumble confidently in my pocket, then wear an expression of utter bemusement. ‘Well it was here. Hang on a minute, I must’ve dropped it on the floor.’ I’d be on hands and knees among discarded sweet papers and cigarette butts.

‘All right, if you dropped it you dropped it. Sit down, son. It’s not a problem.’

If all else failed and a fare was demanded my brother and I could always just leap up, push past the conductor and jump off the bus. Even at speed you could hold the pole and start running in the air, and that would dramatically reduce your chances of going head over heels under a following lorry. Once or twice I had my ears boxed by conductors during a scuffle. And once or twice we leapt off at speed and landed badly. James went into a bus shelter. I went into a bin. But we usually saved our 15p and walked the rest of the way to school, and then just lied about why we were late and got away with it, day after day, which just emboldened us further.

Initially we were just skipping bus fares, playing chicken by lying down on the dual carriageway near our house as cars whizzed close, or making hoax calls from phone boxes to the operator or calling London Zoo and asking to speak to Mr. G. Raffe who was needed urgently at home. The operator on the other end would generally fall for it and we’d hear the request blasting out over the Tannoy. They were just silly pranks for my brother and me, but we soon had a little gang with a few other kids from the same area, and every feral victory was addictively exciting.

Soon we gravitated from bunking bus fares to petty vandalism. We would smash milk bottles, fill car locks with glue and shoplift. For years I held my school record for stealing Kinder Eggs from W.H. Smith in Ealing Broadway: twenty-seven eggs in one go. How I managed it, at eleven, while wearing school uniform, I still don’t know. It was ridiculous, of course, and childish. But for me it was completely intoxicating. My poor old mum had no idea what we were up to. James and I told her we were having extra recorder lessons.

At twelve I moved to a high school nearer home with older kids who weren’t just thieving sweets. We’d be out late into the evening playing football in the park or causing trouble. One day during the summer holidays a group of us broke into the Barbara Speke Stage School in Acton, which has had soap stars, celebs and Phil Collin

s as students. For a few years we had butted heads with kids from the private school and in truth we were delighted a fire had broken out and the school had been closed for renovation. Before the work began a group of us decided to see if we could make the builders’ job a little bit harder.

We broke in easily enough and then quite literally smashed it to pieces: windows, doors, water pipes and dance mirrors. I ripped a long piece of piping off the wall, watched the water flooding out and then used the pipe to smash the huge floor-to-ceiling mirrors in the hall. Shameful now, but utterly thrilling at the time, gifting a feeling of power and destruction. We broke everything and flooded the rooms. We were out the back playing in a couple of old wheelchairs on a fire-damaged waste dump when the police arrived. We were disarmingly young, and told the police we had seen a bunch of older lads smashing the place and then legging it. It’s almost ludicrous with hindsight, but I told the officers ‘they went thataway’, and they believed me. Astonishing. We went back several times to create more mayhem, and other groups of kids did the same. Within a few weeks we were told the damage was so bad the school could no longer be repaired and they had to move to another building further down the road.

Phil Collins kept his link with the school. I met him when we were both guests on the Chris Evans Breakfast Show and apologised. To his eternal credit he drummed on an empty box of photocopier paper and let me sing backing vocals to ‘In the Air Tonight’ live on the radio. Perhaps that was punishment.

Time and again as a kid I got clean away with pranks and crimes. Before too long I found myself in stolen cars. I wasn’t driving and I didn’t steal the cars. I was only twelve or thirteen. But I’d hang out with friends on Acton Vale Estate causing trouble, and then on White City Estate which at the time had a tricky reputation. Cars were regularly set on fire on the estate and the area was considered a major riot risk. This was the mid-1980s, with the Brixton riots a fresh memory, Margaret Thatcher in power and many inner-city areas tense or on a knife-edge. I didn’t burn any cars but I knew the young guys who did. More than once they stole a vehicle, set it alight, waited for the fire brigade to show up then lobbed petrol bombs at the firefighters. I don’t remember feeling guilty at the time, but I certainly do now.

Step by Step

Step by Step