- Home

- Simon Reeve

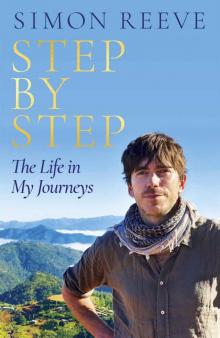

Step by Step Page 6

Step by Step Read online

Page 6

It was a hard time, a painful time, and it is still troubling for me to revisit and admit it all now. But if I hadn’t gone through it no doubt I wouldn’t be who I am as an adult, or doing what I do today. From the relative comfort of older age, every trauma and darkness that I suffered as a teenager now looks like part of my journey to get to where I am. But I have never stopped to look back, to try to understand my past. Sharing it now is humbling and cathartic.

Every story is unique, every life so frighteningly specific. There is peril in offering further thoughts or advice to others. But perhaps, perhaps, if you are suffering from depression, try to tell yourself there is hope. Try to drown the whispers in your head that are negative with the knowledge, with the stronger and louder certainty that you are wonderful, inspiring and interesting, both now and into your future. Find voices that comfort you and people who hug and help. If you are caring for a young me, just listening is a huge support, but perhaps also remember the human mind is a powerful machine. Many years later I was with a young French special forces captain, in the most dangerous place in the world, on a base under attack from suicide bombers: ‘People don’t change when others tell them they should. People change when they tell themselves they must.’

He was talking about countries, but the same thing applies so often to us, as individuals. Sometimes we have to walk our own path, wherever it takes us. In my case I had love around me. I had hugs. But still the darkness was too powerful and overwhelming. It took me to the brink, to a moment from the end.

The days dragged past after I stepped off the bridge and I managed to drag myself along with them. I hadn’t changed, I wasn’t suddenly brimming with confidence or filled with a zest for life and I had no idea what I was going to do. But I had to do something. Anything. If I wasn’t going to kill myself then I needed alternatives. My relationship with Dad improved, to the point that he was able to give me driving lessons without us killing each other. Then he started checking classified adverts and leaving them out for me, but I was nowhere near confident enough to apply for a job. James said I should sign on. I was desperate for a bit of money, so I took a bus into Ealing. From the top deck, I had an elevated view of my world and it felt small and stifling. I wandered over to the DSS office, down a side street opposite the Town Hall, telling myself I was just going to check where it was, but I saw other lads heading inside and followed them in. It had a depressing air and there was a long queue for the counters. But just as I walked inside a man who had been talking to an official near the entrance stood up from her desk. He moved out of the way and she looked straight at me. She had a kindly, wise face and an open smile. She must have dealt with scores of tragedies and desperate souls every single day, but there was no judgement in her eyes.

‘Can I help?’ she said warmly.

I hadn’t really planned to sign on for benefits, but she put me down for Income Support. At £26 a week, I think, it was even less than the dole, but the only option for a seventeen-year-old who had never had a full-time job. I went home and mooched around for a few weeks, still depressed and unsure what to do next. But then I passed my driving test and an idea popped into my head that I can honestly say changed my life. A simple thought that, perhaps more than anything, connects my adult self with that troubled teen. I decided to go on a journey.

CHAPTER FIVE

The Lost Valley

It just came to me one morning. I felt like I had to face my fears and push myself just a little. But knowing that and doing anything about it were two different things. I would go somewhere, and I would do something. But where? What? I had been so low for so long I wasn’t even entirely sure what my specific fears or even my strengths were any more. I was wracked with self-doubt and low self-esteem. Thoughts of doing anything adventurous were frightening.

Initially I had no idea where I would go, or what I would do. Although I had a bit of money from benefits, I wasn’t exactly flush. But my mum was desperate for me to get up and out of the house, in the best sense, and she lent me some cash. I bought a cheap train ticket to Scotland, inspired, I think, by nothing more than watching the movie Highlander.

Whatever the reason for choosing Scotland, even thinking about going there was a few tentative steps towards recovery. I had been a whisker from suicide, and I knew there was a risk I would be back there again. What if I had a panic attack on the train? What if I couldn’t handle it?

I thought back to the lady in the DSS office. I was used to therapy, and even in my brief fifteen minutes with her I had talked openly. I told her I’d left school, with no real qualifications, and that I was pretty low and had no idea what to do next. As I write these words I can feel myself back there, sitting opposite her, as if I have passed through a portal in time, with my hands on her desk as I explained some of my fears. I can remember the sharp raised voices around us, the smell of stale cigarettes and disinfectant in the office, the screw-down chairs in the waiting area, and – most of all – her patient air. I can remember everything about that moment because she gave me simple advice that guided me then, and still does to this day.

‘If it’s difficult for you,’ she said, ‘just take it all slowly. Take things step by step.’

I latched onto those words as wisdom. Even in my hopeless state I realised that was the answer. I was no longer a child. I could start behaving like an adult. Everyone seems to think that childhood is without responsibility, but actually you are forever told where to be, what to do and what to study. Now I could claim the freedoms of an adult. If I didn’t like something, or didn’t want to do something, I could just say no. If I started a journey and changed my mind, I could just turn back. It was OK. I would just take it all . . . step by step.

So, off I went, my first real adventure by way of a train to north of the border. I’d never been anything like that distance on my own. I’d never even been out of London on my own.

As the miles ticked by, I became more and more aware my journey mattered. I got off the train, spent the night in a cheap B&B then hired a car in the morning. A tiny red Peugeot took almost all of the money I had but it got me to Glencoe, which was my jumping-off point. For what, I don’t know. I’m not sure what was guiding me, but I like to think it might just have been a bit of fate. By the time I arrived in Glencoe it was far too late in the day to set out anywhere and all I was wearing as outer layers were jeans, a pair of trainers and an old Adidas cagoule. I’d just go for a quick hike, I told myself. I left the car in the car park and ambled up the mountain.

When I started my journey I was an insecure teenager. But the climb changed me. I wasn’t conscious of anything as significant as that at the time, but I know it now. Deep within me I must have realised that I had to conquer something. That’s what this was about, setting myself a task that seemed unlikely and making sure I achieved it. It would be a tonic, even a cure. Perhaps, deep down, I knew that evening that if I was able to stand on a summit somewhere I would prove something to myself. But initially I just set out, not thinking any further ahead than the next step. I crossed a river, scrambled up a slope and trotted through a wood. I found myself becoming a little bolder. I started selecting specific points in the distance that I promised myself I would get to.

‘Step by step,’ I muttered to myself. If I can reach that tree over there I’ll stop and turn back, I thought. Then when I reached the tree I saw an outcrop of rocks. ‘I’ll just get to them,’ I said out loud.

Soon it was early dusk. I passed hikers and climbers on their way down. More than one raised an eyebrow when they saw me. I said I was just going to see how far I could go before nightfall.

‘Be careful, it’s dangerous,’ one guy in breeches and walking boots told me severely. He was carrying a walking pole and gestured up the way he had come. ‘It’ll be dark before you know it. You’re not dressed properly. You’ve no pack and no sleeping bag, someone will be calling out mountain rescue.’

No, they wouldn’t, I thought. I hadn’t told anyone I was up

here.

I promised to turn back, but pressed on, passing others on their way down. I didn’t care. I was on a mission. Every step gave me an increased sense of self-worth and purpose. Only I could understand and I wasn’t about to explain it to anyone.

I followed a track up rough steps and crested a summit and was initially gutted to realise I had only reached a long flat glen. I now know it was Coire Gabhail, The Lost Valley, where the Clan MacDonald used to hide their cattle, or any they had rustled. It’s a rough and rocky walk; all the guides tell you great care is needed and you shouldn’t be up there in twilight, never mind darkness. But I didn’t think about that.

I looked along the valley and knew I should turn back. There were boulders the size of houses. The glen was surrounded by peaks, but right at the back directly in front of me, I could still see a fold in the mountainside leading up to a high ridge. I wasn’t thinking about a summit. I just wandered to the end of the valley to have a look, and then, almost absent-mindedly, I started to climb. Step by step. I didn’t think about how I would get down if I made it to the top; I concentrated on taking each step, focusing on targets nearby: a rock, a bush. Onward and ever upward, one foot in front of the other, scrambling on my hands and knees up loose scree, until eventually I was completely committed to the climb and was focused on reaching the ridge above me. I didn’t care how dark it got, this was something I was determined to accomplish.

I reached the ridge in darkness, and I stood there feeling euphoric and a tiny bit brave, aware I had really accomplished something. Above me loomed higher peaks, but for the first time in years I felt a sense of physical success. I stared at the stars, lost in the moment and delighting in a sense of achievement. This wasn’t how the government wanted me to spend my benefits, but it was a complete tonic. I’d completed a journey, the very first one I had taken alone and the furthest I had ever been. Suddenly Acton seemed small and faraway and the distance offered perspective. With it the panic that had been haunting me seemed to slip away. Then, of course, reality kicked in.

‘It’s bloody dark,’ I thought to myself. ‘How the hell am I going to get down?’

I started back the way I had come but it was really dark and cold. I couldn’t see where I was going and it wasn’t long before I discovered it was harder to go down the mountain than climb up. I scrambled from side to side on the loose scree until the clouds thinned and I was able to see rocks and holes. I made it back to the valley unscathed and spent a freezing night alone in the car. I didn’t care. I was elated.

A day or two later I was back on a train heading south, and, to my amazement, realised I was chatting confidently with a young woman sitting opposite. That climb up the mountain taught me that no matter how bad things might have looked for me, there was hope. When you’re a youngster struggling to come to terms with life, it’s easy to slip into a trough of despair. But if you can pick yourself up just enough to take a few initial steps, sometimes, just maybe, you can start to climb out of your situation. Life advice often consists of people saying you should ‘aim for the stars’ and plan where you want to be in a year or even five years, but for me that was completely unrealistic. I could hardly see beyond the end of each day. So I set much smaller goals. It worked for me. I had climbed a mountain and my life began to improve.

It wasn’t easy and things didn’t change overnight. People talk about ‘getting their mojo back’, and mine had been missing for a while. But I could feel a gentle rise in my confidence. I took things slowly. Step by step. My income support helped, as did the sympathy and support of my parents. Dad was calmer, more willing or able to love and compromise, with all of us. He suggested I try for a temporary job, and I managed to get a part-time role collecting trolleys and stacking shelves in a Waitrose supermarket. I loved it. But I still couldn’t get a full-time job, so during the week I started volunteering in charity shops. It kept me out of the house, taught me how to negotiate tricky relationships and made me feel like I was actually doing something. It was my job to organise the roster, a role fraught with difficulty. Imagine organising forty occasional volunteers of a certain age. It was a diplomatic challenge to rival negotiating with Pyongyang. Each week I’d figure out what I thought would work in terms of staff then I’d pick up the phone.

‘Hi Rose, it’s Simon at the Cancer Research Campaign shop. I’m doing the roster for next week. Do you think you might be able to come in?’

‘Oh, I can come in for half an hour next Wednesday lunchtime.’

‘Lunchtime, Wednesday, half an hour. OK, that’s a popular slot. I’ll see what I can do.’

Midday on a Wednesday was when our main bundle of donations arrived from the charity distribution centre. Some volunteers wanted to come in around that time so they could have first dibs on the best clothes. I had to help manage a team, many of them fragile souls, and all for a really good cause. It helped with my self-esteem, as well as giving me advanced training in diplomacy. I stayed for six months or so while schlepping from one job centre to another in a hunt for work and applying for full-time jobs. But I was discovering that when you leave school with no qualifications, no connections and no real idea of what you want to do there’s not a lot of help out there.

Everyone told me that any job would be a start, so I went for anything available: porter, janitor, sweeping the floors in the shopping centre. I applied for at least two dozen driving jobs before I finally had a call from the job centre for an interview to drive a small van delivering parcels for a firm on Wembley Stadium Trading Estate. The pay was terrible, but I honestly thought it was a job that was made for me. The sullen owner turned me down straight.

‘You’re the only one who’s applied.’ He had the keys in his hand. ‘But I’m still not giving you the van.’

I was gutted. I didn’t even need to ask him why. The question was written across my face.

He folded his arms across his chest and wagged his head from side to side. ‘I don’t have to give you a reason. I’m just not giving you the job.’

I still have no idea why he turned me down and took such malicious delight in telling me to my face. Maybe the job centre had forced him to give me an interview. I had run out of money for my bus fare, and it was a long walk home.

Finally, I managed to get a full-time job with H. Samuel the jeweller’s in Oxford Circus. I gave up my part-time job in the supermarket and arrived keen and expectant to start selling watches and earrings. On my first day the manager told me there was one unbreakable, unbendable rule: never, ever, take the keys to the safe home. After a long day I was on the Central Line home to Acton when I found the full bunch in my pocket. It was surely the shortest retail career ever. I went back in the morning and the astonished manager sacked me on the spot. He said it had never happened before, and either I couldn’t be trusted or didn’t listen but neither was good enough.

Still, I was feeling better than I had in years. I began to think anything was possible. When I wasn’t in the charity shop or a job centre, I was in Westminster library looking through magazines and newspapers trying to find a job. I must have read something that sparked an interest in spying, probably Peter Wright’s infamous book Spycatcher, because I suddenly decided I quite liked the idea of working for MI6. I actually turned up at the then secret headquarters of MI6 in Century House, in Vauxhall, an anonymous office building next to the Tube.

Imagine the scene: a teenager in scruffy jeans and a cheap leather jacket wanders into the global headquarters of the Secret Intelligence Service. The receptionist did a double-take from behind a thick Plexiglas window. Standing in the background beyond her was a police guard cradling a sub-machine gun. His expression spoke for him. What the hell do you want?

‘Hi,’ I said to the receptionist. ‘Erm, I’ve just come in to see if I can apply for a job.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘I just wondered if I could apply for a job. Working for, y’know . . .’ and then I actually leaned forward and lowered my voice, ‘M-I-6

.’

She stared at me with her mouth slightly open, trying to decide if I was for real. Then she started shaking her head. ‘No,’ she said, ever so slowly. ‘No, no; that’s really not how things work. You would need to contact the Foreign Office.’

‘Oh, OK,’ I said brightly with a glance at the guard. ‘I’ll go and have a chat with them, then.’

It makes me cringe now. But I also have a sneaking admiration for myself at that moment. Just a few months before I’d been on a bridge about to kill myself. I was all over the place. One month I was in a state of desperate depression, and the next I was walking into MI6 in some vague hope of becoming a spook.

After that my approach was completely scattergun. I did actually get a job working as a clerical assistant for the Ministry of Defence, albeit by replying to a conventional advert in the job centre rather than ambling into the MoD in Whitehall or stopping an admiral in the street for a chat. I was so nervous when I started the job that I vomited most of the way there on my first day. They made me sign the Official Secrets Act then posted me to a top-secret department at the Empress State Building in Earls Court that handled communications between the nuclear fleet and the land-based command. It sounded important, but then they showed me into the office where I would be working. I was going to be locked into a small room with three middle-aged men with grey hair and grey skin, and my job was to photocopy documents. Thousands of them. Endlessly. Each time the photocopier whirred and clicked a second copy would be put into a locked safe. There was no natural light because of blast curtains, even though we were high in the building, and security was so tight, if we wanted to go to the loo we had to buzz through to a desk and somebody would unlock the door and escort us to the toilets. I was desperate for a proper job, but after an hour in there even I realised I would go mad within a week.

Step by Step

Step by Step